in Thoreau’s Journal:

Our feet must be imaginative, must know the earth in imagination only, as well as our head.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

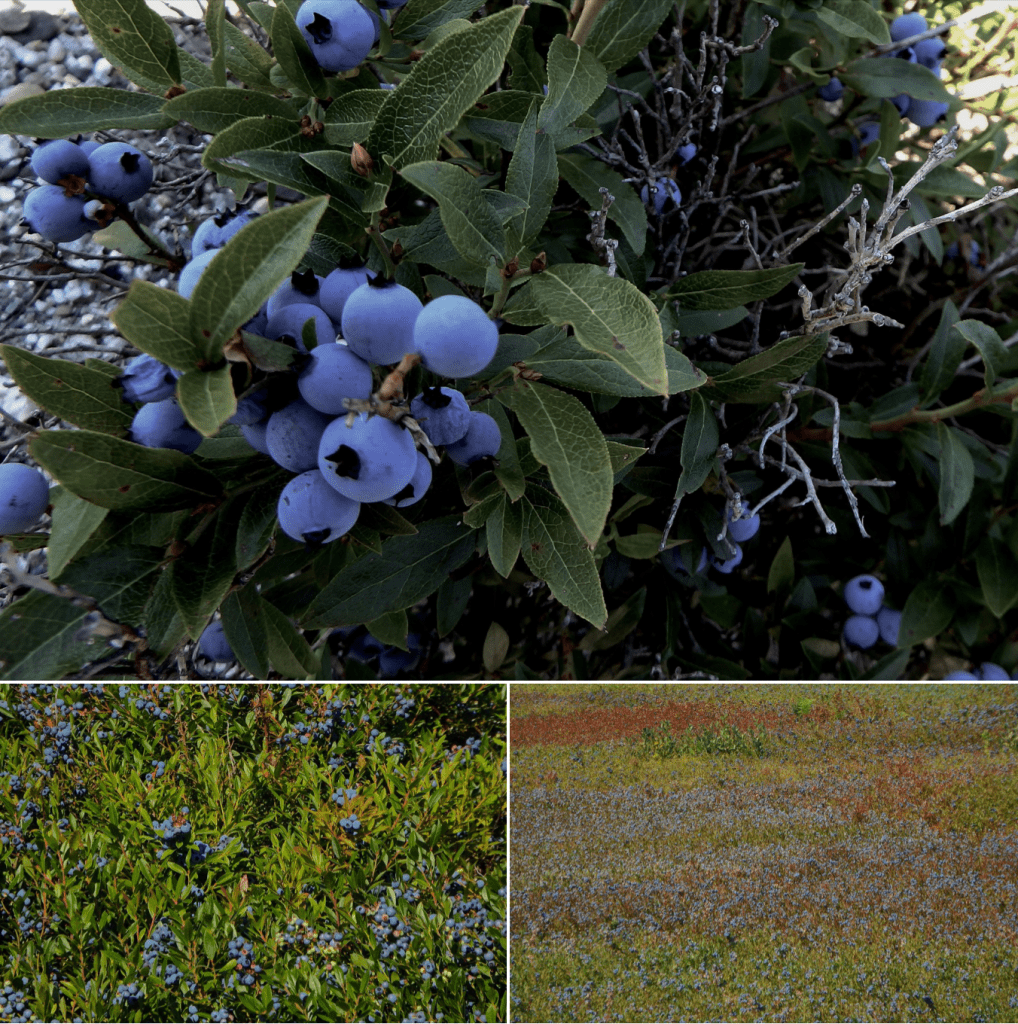

The berries of the Vaccinium vacillans are very abundant and large this year on Fair Haven, where I am now. Indeed these and huckleberries and blackberries are very abundant in this part of the town.

Nature does her best to feed man. The traveller need not go out of the road to get as many as he wants; every bush and vine teems with palatable fruit. Man for once stands in such relation to Nature as the animals that pluck and eat as they go. The fields and hills are a table constantly spread.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

The red-lily with its torrid color & sun freckled spots––dispensing too with the outer garment of a calyx––its petals so open & wide apart that you can see through it in every direction tells of hot weather–– It is a handsome bell shape––so upright & the flower prevails over every other part. It belongs not to spring.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

The first really foggy morning yet before I rise I hear the song of birds from out it—like the bursting of its bubbles with music—the bead on liquids just uncorked. Their song gilds thus the frostwork of the morning— As if the fog were a great sweet froth on the surface of land and water—whose fixed air escaped—whose bubbles burst with music. The sound of its evaporation—the fixed air of the morning just brought from the cellars of the night escaping.— The morning twittering of birds in perfect harmony with it. I came near awaking this morning. I am older than last year the mornings are further between— The days are fewer— Any excess—to have drunk too much water even, the day before is fatal to the morning’s clarity—but in health the sound of a cow bell is celestial music. O might I always wake to thought & poetry—regenerated! Can it be called a morning—if our senses are not clarified so that we perceive more clearly—if we do not rise with elastic vigor? How wholesome these fogs which some fear—they are cool medicated vapor baths—mingled by nature which bring to our senses all the medical properties of the meadows. The touchstones of health— Sleep with all your windows open and let the mist embrace you.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

Keep on through North Tamworth, and breakfast by shore of one of the Ossipee Lakes. Chocorua north-northwest. Hear and see loons and see a peetweet’s egg washed up. A shallow-shored pond, too shallow for fishing, with a few breams seen near shore; some pontederia and targetweed in it.

Travelling thus toward the White Mountains, the mountains fairly begin with Red Hill and Ossipee Mountain, but the White Mountain scenery proper on the high hillside road in Madison before entering Conway, where you see Chocorua on the left, Mote Mountain ahead, Doublehead, and some of the White Mountains proper beyond, i. e. a sharp peak.

We fished in vain in a small clear pond by the roadside in Madison.

Chocorua is as interesting a peak as any to remember. You may be jogging along steadily for a day before you get round it and leave it behind, first seeing it on the north, then northwest, then west, and at last southwesterly, ever stern, rugged and inaccessible, and omnipresent. It was seen from Gilmanton to Conway, and from Moultonboro was the ruling feature.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

Descended, and rode along the west and northwest side of Ossipee Mountain. Sandwich, in a large level space surrounded by mountains, lay on our left. Here first, in Moultonboro, I heard the tea-lee of the white-throated sparrow. We were all the afternoon riding along under Ossipee Mountain, which would not be left behind, unexpectedly large still, louring over your path. Crossed Bearcamp River, a shallow but unexpectedly sluggish stream, which empties into Ossipee Lake. Have new and memorable views of Chocorua, as we get round it eastward. Stop at Tamworth village for the night.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

The fresher breeze which accompanies the dawn rustles the oaks and birches, and the earth respires calmly with the creaking of crickets.

Some hazel leaf stirs gently, as if anxious not to awake the day too abruptly, while the time is hastening to the distinct line between darkness and light.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

The river and shores, with their pads and weeds, are now in their midsummer and hot-weather condition, now when the pontederias have just begun to bloom.

The seething river is confined within two burnished borders of pads, gleaming in the sun for a mile, and a sharp snap is heard from them from time to time. Next stands the upright phalanx of dark-green pontederias. When I have left the boat a short time the seats become intolerably hot. What a luxury to bathe now! It is gloriously hot, —the first of this weather.

in Thoreau’s Journal:

The true poem is not that which the public read.

There is always a poem not printed on paper, coincident with the production of this which is stereotyped in the poet’s life —is what he has become through his work…Let not the artist expect that his true work will stand in any prince’s gallery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.