in Thoreau’s Journal:

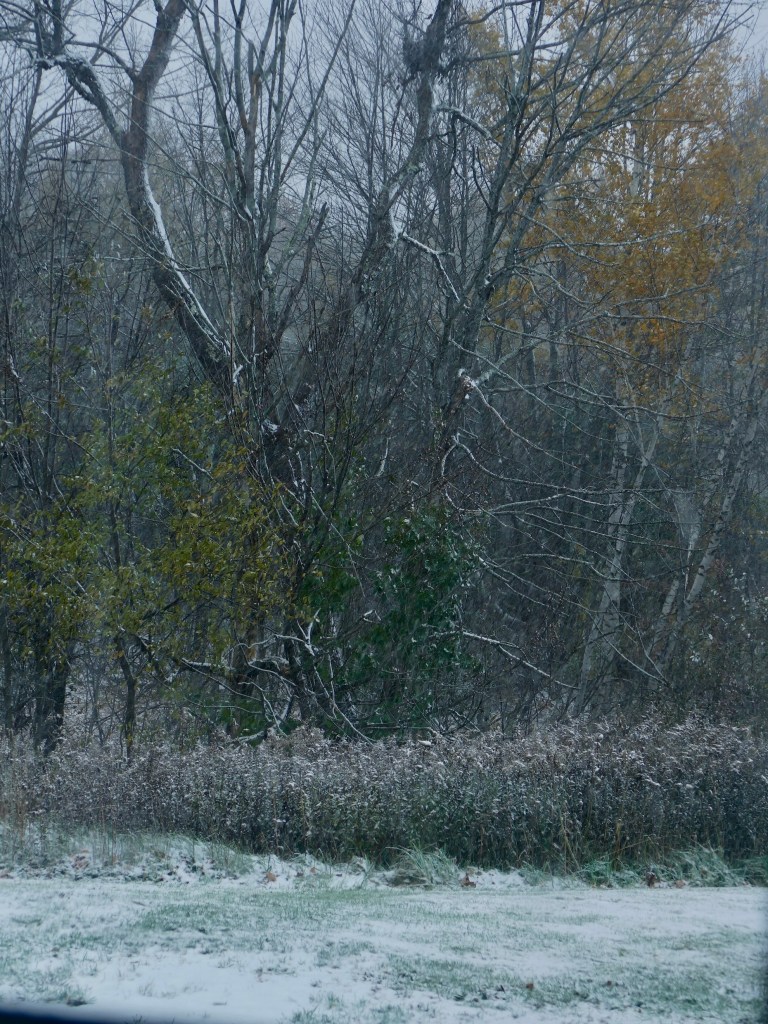

The wild apples are now getting palatable. I find a few left on distant trees—which the farmer thinks it not worth his while to gather—he thinks that he has better in his barrels, but he is mistaken unless he has a walker’s appetite & imagination—neither of which can he have. These apples cannot be too gnurly & rusty & crabbed (to look at)— The gnurliest will have some redeeming traits even to the eyes— You will discover some evening redness dashed or sprinkled—on some protuberance or in some cavity— It is rare that the summer lets an apple go without streaking or spotting it on some part of its sphere—though perchance one side may only seem to betray that it has once fallen in a brick yard—and the other have been bespattered from a roily ink bottle.

The saunterer’s apple, not even the saunterer can eat in the house.— Some red stains it will have commemorating the mornings & evenings it has witnessed—some dark & rusty blotches in memory of the clouds, & foggy mildewy days that have passed over it—and a spacious field of green reflecting the general face of nature—green even as the fields— Or yellow its ground if it has a sunny flavor—yellow as the harvests—or russet as the hills. The noblest of fruits is the apple. Let the most beautiful or swiftest have it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.